Some Thoughts on the HECS-HELP Reforms

mostly good, some weird

The Albanese government made three changes to the HECS-HELP system (Australia’s income-contingent loan scheme for university tuition) which are set to kick in next year:

Raise the minimum repayment threshold from an annual income of $54,435 to $67,000.

Replace the existing repayment system with a marginal repayment system to eliminate effective marginal tax rate cliffs.

Cut 20% off of all outstanding debts.

I’ll go through each of these changes in order and give my thoughts on them.

Raising the Minimum Repayment Threshold

When HECS-HELP was first introduced, the minimum repayment threshold was set to the median annual wage. The point of doing this was to justify the policy on equity grounds. You only needed to start repaying your university fees once you started earning the same income as the median Australian. Over the decades the median wage has gradually moved further and further away from the minimum repayment threshold. Raising the threshold to $67,000 puts it more or less at the median annual wage again. This is a good move. That said, I would have liked to see the government actually index the minimum repayment threshold to the median annual wage instead of this one-off increase.

The Marginal Repayment System

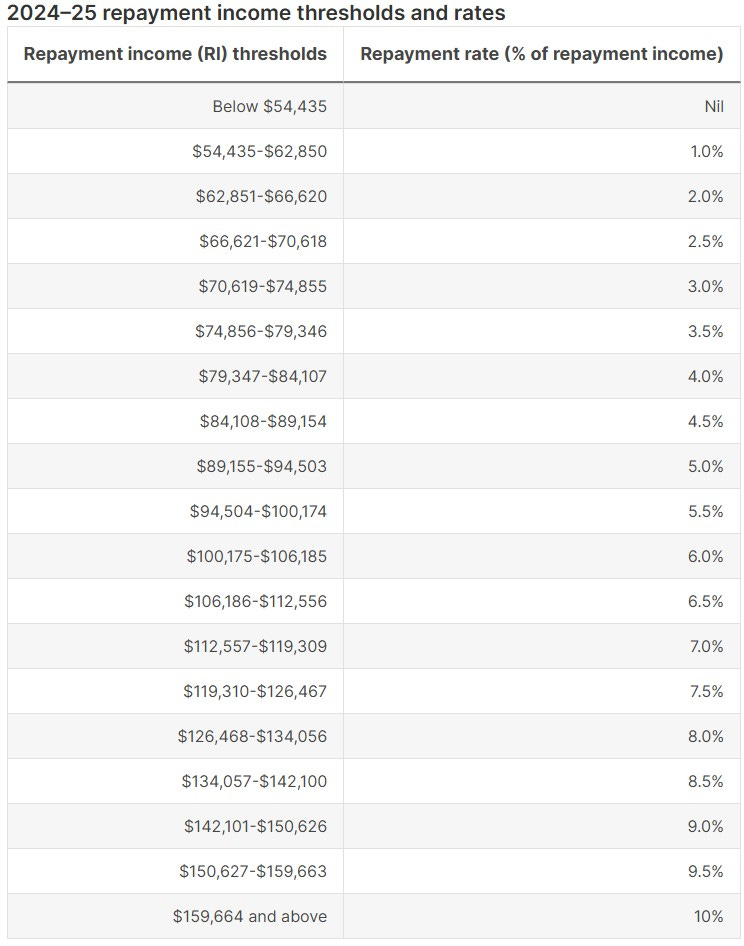

The second change does a lot to address the scheme’s infamous effective marginal tax rate cliffs. The way that the repayment thresholds currently work is that you pay a fixed percentage of your income depending on the band that you fall into:

This means that as soon as you earn $1 over a previous band you start paying the higher rate. So if you earn $62,850 then you need to pay $628.5, but if you earn $1 more then you need to pay $1,257.02. This is unfair and inefficient, though it’s unclear how many people are impacted by these mini effective marginal tax rate cliffs.

The government is moving to a marginal repayment system, like the system we have for income tax, where anyone earning between $67,000 will need to pay 15 cents for every dollar over $67,000. Those earning over $125,000 will need to pay $8,700 plus 17 cents for every dollar over $125,000. This technically increases most debtors effective marginal tax rates but reduces the actual dollar amount that they’re required to pay.

There is some disagreement over whether lower repayments are good because it means that many people will take longer to pay off their debt. I think it’s good because it’s better for income smoothing reasons. The way HECS-HELP is designed means that people start paying it back relatively early in their earning years where they’re not earning as much as they will in their peak earning years. Allowing people to take more time paying back their debt means that the bulk of the debt doesn’t have to be front-loaded as much in these early earning years. All things considered I think this is a great change.

Cutting 20% Off of All Outstanding Debts

This change is the most controversial of the three and I have to admit that I’m not the biggest fan of it either. The biggest beneficiaries of this policy are those who are paying back very high debts. In other words, it will benefit those who have enrolled in the most expensive courses like deregulated postgraduate coursework programs and those who have done more courses than the average student. I’m not sure why the Albanese government went for forgiving a fixed percentage off of student debts rather than a specific dollar amount.

This kind of defeats the point of having differential fees in the first place, which makes me wonder why the government isn’t reintroducing fee regulation for postgraduate coursework or rolling back the previous government’s absurd ‘Job-Ready Graduates Package’ that tried to use differential student contribution amounts as price signals to discourage students from pursuing arts degrees. Whatever you think of the merits of differential fees (I’m not a fan), it makes little sense to charge some students more and then offer them a big discount after the fact.

Predictably, the decision has been met with pundit complaints about how inequitable it is. Many of which are coming from people who otherwise don’t seem to care about equity at all and, if anything, want a more regressive tax-transfer system. I am generally unsympathetic to this sort of equity argument because, as I’ve said before, “there is no purely distributive reason why university graduates should incur a higher effective tax rate than high-earning non-graduates” and the earnings premium on attending university is relatively small when compared to other OECD nations.

All that being said, I do think the debt forgiveness is a little odd considering it’s been combined with the decision to raise the minimum repayment threshold to $67,000. It will benefit people with large student debts who are earning above the median income, so it’s clearly regressive.

I don’t like how we’ve collectively decided to import American talking points about student debt forgiveness. When I was an undergraduate I was involved in a bunch of student activism, which included things like organising rallies and having debates about abolishing university fees and the like. The issue of debt forgiveness never really came up because no one saw it as an important issue. Partial or complete debt forgiveness wouldn’t actually do anything to make university free. All it would do is make it cheaper or free for those repaying existing debts and it’s not at all clear to me why we should target that particular cohort. Cutting 20% off of all existing student debts just comes across as a cynical and arbitrary measure to win votes from current debt holders.

There's value in a cut, in that it builds appetite for future cuts and reforms that might ultimately get rid of the program all together.